![]() Orthodox

Heritage

Orthodox

Heritage![]()

Home Message of the Month Orthodox Links Prophecies Life of St. POIMEN About Our Brotherhood

Receive Our Periodical Order Orthodox Homilies / Publications

Contact UsMESSAGE OF THE MONTH

(February 2019)

The Birth of the West’s Post-Patristic Battle against the Holy Fathers

By Protopresbyter Theodoros Zisis, Emeritus Professor of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. This article is the first part of an insightful presentation by Fr. Theodoros at the “Patristic Theology and Post-Patristic Heresy” a 2012 Symposium of the Holy Metropolis of Piraeus.

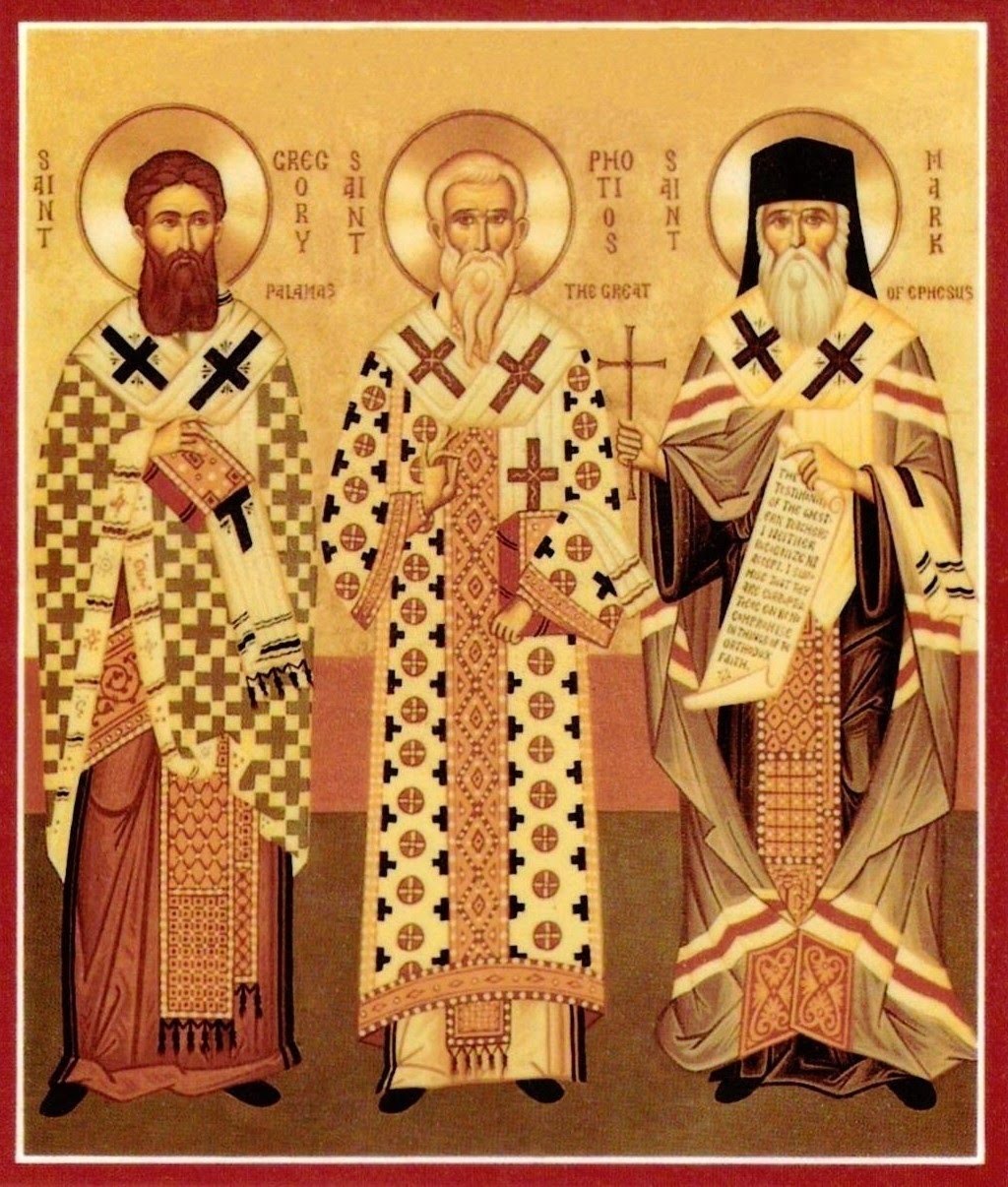

The Three New Pillars of Orthodoxy: Sts. Gregory Palamas, Photios the Great, and Mark of Ephesus

† † †

The Scholasticism of the Franco-Papist West against the Patristic East

In the West, until the 8th century, theology and spirituality, in essence, followed the route marked out by the East. As G. Dumont points out, the sources and principles of theological thought, liturgy and spirituality for the West, which characterize the flourishing era of Latin Catholicism, are to be found in the East, however much this may come as a surprise to many Western Christians.

The West owes the East a debt as regards the fact that it formulated into dogmas the great mysteries of Christianity concerning the Holy Trinity, the union of divine and human nature in the one person of Christ, a large number of feasts in the Church’s year, especially in honor of the Mother of God, as well as the foundation and organization of monasticism.

The estrangement between East and West begins at a particular time in history: the dynamic appearance on the historical stage of the German Franks of Charlemagne offered the throne of Rome a powerful ally against the pressures of the Byzantine emperor and gave the German prince and his successors the opportunity to found and construct the Holy Roman Empire of the German people as a replacement for Romania (New Rome/Constantinople) which was henceforth known as Byzantium.

According to the analysis of Le Guillu, Charlemagne’s ambition was to create a new theological tradition independent of the Patristic Tradition of the East. As he explicitly says: “In the Carolingian books, the first attempt is made by the West to define itself in opposition to the East.” The greatest contribution to this estrangement was made by the abandonment of the Patristic Tradition and by the construction of a new theology on the Aristotelian syllogistic method, i.e. the formation of the Scholastic Theology.

In the 14

th century conflict between Saint Gregory Palamas and Barlaam the Calabrian, we have the clash of the new, scholastic theology with that of the Patristic Tradition of the East which was rooted in the Holy Spirit, and which, until then, the West had followed, too.The Clash between Orthodox Illumination and Western Enlightenment in the 14

th CenturyThere was, indeed, a severe conflict between the scholastic, post-Patristic theology of the Westerners and the empirical theology of the Fathers of the Church which was inspired by the Holy Spirit. The former was expressed by Barlaam the Calabrian, one of the chief architects of the Western Renaissance and the latter by the great God-bearing and God-revealing Theologian, Gregory Palamas, who achieved in the 14th century what John Damascene had in the 8th: the expression and codification of the teachings of the Fathers who came before on many issues, the most important being:

(a) whether theology ought to be dialectic or demonstrative, i.e. whether it should be founded on philosophical analysis and discussion, as Barlaam wanted, bringing the scholasticism of the West into the East, or founded on the certainty of the experience of the Holy Spirit which the Prophets, Apostles and Saints had enjoyed, as taught by Palamas;

(b) whether human wisdom leads to perfection and deification, as Barlaam claimed, or whether these were achieved only through divine wisdom, which is granted to those who keep the commandments of God and are cleansed of the passions, in which case, after purification, they receive divine illumination and thereafter attain to the vision of God, as Saint Gregory Palamas contended; and,

(c) whether this illumination is the fruit of the created energy of the intellect, as Barlaam would have it, or of the uncreated energy of God, as stated by Saint Gregory, which really deifies people by energy, by grace, but not by nature and essence, because the uncreated energies are distinct from the essence of God.

Saint Gregory’s arguments were overwhelmingly successful and a famous victory was won by the Patristic East, inspired by the Holy Spirit over the scholastic and post-Patristic West. We shall not analyze this here, but merely observe that without observance of God’s commandments, the ascetic way of living, and the effort to purify oneself of evils and passions, as the Holy Fathers, those theologians of experience, lived and taught, without these no-one can become wise in divine matters. So the only chance that someone who is not illumined and glorified has, when wishing to speak about theology, is to follow those who were illumined and deified by the grace of the Holy Spirit. If this condition is not in place, we have no wisdom or theology, only foolishness and childishness.

Addressing Barlaam, and all the post-Patristic theologians of all ages—the thinkers, philosophers, academics—Saint Gregory observes pithily in the Holy Spirit: Without purification, even if you learn natural philosophy from as far back as Adam and up until the end of the world, you will be none the wiser. Over the last few days I have been looking closely at Saint Gregory Palamas’ writings, to confirm what I wanted to say here “following the divine fathers and this God-revealing and God-seeing Father.” It would take a long time for me to present the Patristic attitude of Palamas, the honor and value he accords the Holy Fathers.

Of the many things I have perused, I would present merely a few which are indicative, in order to show how mistaken and how far outside the Orthodox Tradition are those clergy and laity who, (at their academies and theological schools) instead of making the Spirit-inspired and God-illumined Holy Fathers the object of their studies, those who have given us access to the vast, uncreated world of divine majesty, instead bring us down to the created and petty things of human thoughts and philosophies and, often enough, initiate us into the depths of Satan, as Saint Gregory says. For example, they get rid of the confessional lesson of Religious Instruction from schools, catechism, dogmatics, liturgics, history, references to the Mother of God and the Saints, Scripture—Old and New Testaments—and have, instead, through the lesson dubbed “Religious Knowledge,” introduced Masonic, Satanic syncretism.

In confirming his truly wondrous accord with the Fathers over all the intervening centuries, Saint Gregory says that it is impossible for the God-bearing Fathers not to agree among themselves, because they are all guided by the inspiration of one and the same Holy Spirit. The Fathers are the sure guardians of the Gospel and Theology because the Spirit of genuine truth is manifested and resides in their spirit, so any people who apprentice themselves to them are taught by God. With authority and mastery he stresses that: this perfection is for salvation, both in knowledge and dogmas, saying everything regarding God and His creatures, as the Prophets, Apostles and Fathers held, and as all those through whom the Holy Spirit witnessed.

Barlaam would not have ended in heresy, and with him all the modern, post-Patristic Neo-Barlaamites, had he believed that the divine is not to be approached through human reasoning but with Godly faith; had he accepted, in simplicity, the traditions of the Holy Fathers, which we know are better and wiser than human musings, because they come from the Holy Spirit and have been proved by words rather than deeds. In a snapshot of the Barlaam-like terminology of today’s post-Patristic theologians, Saint Gregory asks Barlaam if the latter has understood where this piety greater than the Fathers will lead. Barlaam was led there, to such a pit of impiety, because, with reason and philosophy, he investigated what is beyond word and nature and did not believe, as did Saint John Chrysostom, that it is not possible to interpret in words the manner of the prophetic sight except and unless you have learned it clearly through experience. For if word is able to present the works and passions of nature, how much more is this true of the energy of the Spirit?

What we have said so far has been aimed at demonstrating that doubts began to be cast on the standing of the Fathers from the 9th century, with the development of scholastic theology and then the anthropocentric Humanism of the Renaissance. The scholastic theology of Papism is responsible for the neglect of the Fathers, not only because it made logic and dialectics the basic tools for theologizing and ignored the illumination from above, divine wisdom, but also because it dogmatized the elevation of the Pope over the synods and Fathers, even over the Church itself. The criterion for correct theological thinking was no longer one of being in agreement with the Fathers, but with the Pope.

Whereas the Tradition of the Church functioned along the line of Christ – Apostles – Fathers, the Papal monarchist view went Christ – Peter – Pope. This powerful post-Patristic storm did not shake the Patristic tradition, the Patristic foundations of the Church, because God revealed, in the middle and late Byzantine times, three new, great hierarchs and ecumenical teachers:

[1] Saint Photius the Great, who was the first, in the 9th century, to oppose systematically and most theologically the anti-Patristic and heretical Papist teaching on the issue of the filioque and that of the primacy of the Pope, endorsing the Orthodox teaching with a decision of the synod in Constantinople in 879, which is considered ecumenical;

[2] Saint Gregory Palamas, who, in the 14th century, opposed the humanist philosopher, Barlaam, at the time when Scholasticism was at its height, and who promulgated the illumination of theologians through the uncreated grace and energy of God, as opposed to the created and limited illumination of human wisdom, a position completely endorsed by the hesychast synods of 1451, in Constantinople, which are also considered ecumenical; and,

[3] Saint Mark of Ephesus, that giant and Atlas of Orthodoxy, rightly called Anti-Papist and the Scourge of the Pope, who alone negated and nullified the decision of the pseudo-unifying synod of Ferrara-Florence, which scurrilously and oppressively dogmatized anti-Patristic and heretical teachings, and which to this day is numbered among the ecumenical synods by the Papists.

Patristics and Post-Patristics at the Pseudo-Synod of Ferrara-Florence

Sylvestros Syropoulos, who wrote the history of the pseudo-synod of Ferrara-Florence (1438-1439), where, on a Synodal level, Patristic Orthodox theology came into conflict with the post-Patristic scholastic theology of Papism, has preserved for us facts and information which help us to realize how far the Church is Patristic and how far the West, since the Franks seized the, until then, Orthodox Patriarchate of Old Rome in the 9th century, was converted into being post-Patristic, and anti-Patristic, giving rise to a whole host of heresies and schisms.

The Orthodox patriarchs knew that Papism and scholastic theology had transcended and pushed aside the Fathers of the Church and had replaced them with their own “Fathers,” chief among whom was Thomas Aquinas (13th century); thus, in their letters appointing their representatives, (their locum tenentes) they (the patriarchs) also set out the limits for the discussions and decisions of the Synod, whether this was to take place in Basel, Switzerland, where the reformist delegates awaited the Pope, or in some other place designated by the Pope. Union was to take place “canonically and legally, in accordance with the traditions of the holy ecumenical synods and the holy teachers of the Church and nothing was to be added to the faith nor removed or introduced as new.” Otherwise they would not accept the anti-Patristic and post-Patristic decisions of the synod.

By taking this stand, the patriarchs expressed the firm, permanent and inviolate position of the Church over the centuries that the Fathers constitute a sine qua non element of the identity of the Church and its theology. There is no theology which transcends the Fathers, and those who denigrate them, or, condemn them, or, even worse, transcend and surpass them, as at the well-known Conference in June 2010, at “The Academy of Theological Studies” of the Holy Metropolis of Volos, are no theologians.

According to Saint John Damascene, the mouthpiece of all the Fathers and voice of the self-awareness of the Church, anyone who does not believe in accordance with the Tradition of the Church is an unbeliever. Earlier than this, the truly great Athanasius, in his well-known letter to Serapion, makes it clear, in wonderful fashion, what this Tradition is on which the Church is founded: it is what Christ handed down, what the Apostles preached and what the Fathers preserved. The Orthodox Patriarchs’ most Orthodox and Patristic framework for the discussions and decisions of the council immediately met with resistance on the part of the papal theologian of the Council of Basel and legate to Constantinople, John of Ragusa, who, expressing the Western Frankish spirit of theology which no longer needed the Fathers, intervened with Emperor Ioannes VIII Palaeologus to ask the patriarchs and he succeeded in his aims—to change their letters, omitting the terms and limitations regarding agreement with the synods and the Holy Fathers.

Unfortunately, the emperor gave way, in the face of his great need for financial and military assistance. But even worse, the patriarchs themselves retreated, even though their criteria ought to have been unalterable and firm, purely spiritual and never political, as regards matters of faith. Syropoulos sadly notes that this was an unfortunate prelude for what was to follow and indicated that the emperor had abdicated his role as fidei defensor: “It was to such preconditions that the defender of the dogmas of our Church had submitted us.”

Of course, the theologians on the Orthodox side, particularly Saint Mark of Ephesus, had no need of patriarchal suggestions in order to take a stand firmly on the Fathers and to force the Latin theologians into a difficult corner, since the latter did not have Patristic arguments and attempted to endorse their positions dialectically and philosophically in accordance with the prevailing Scholastic Theological method, which was based on the logical categories of Aristotle.

Syropoulos actually preserves a charming and most instructive event for all of us, especially the post-Patristic innovators of our own times. According to him, when the representative of the Orthodox Church of Georgia (Iberia) heard Juan de Tarquemada, from Spain, frequently invoking Aristotle, he turned to Syropoulos in consternation and said: “What Aristotel, Aristotele? Aristotele no good”. When Syropoulos then asked him what was good, he replied: “Saint Peter, Saint Paul, Saint Basil, theologian Gregory, Chrysostom. No Aristotel Aristotele.”

He mocked the Latin scholiast with hand movements, nods and gestures, but, as Syropoulos observes, “he was probably mocking us Orthodox, who had abandoned the Fathers and polluted ourselves with such teachers.”

Earlier, he relates another incident, with the same Georgian delegate leaving the Pope speechless and acting as a teacher to him. Just before the apostasy was completed and the shameful unifying text was signed, the Pope summoned this cleric and with the sweetest affability, which recalls the blandishments and geniality of our contemporary ecumenists, advised him to recognize that the Church of Rome was “the mother of all Churches and indeed the successor to Saint Peter and the locum tenens of Christ and the shepherd and universal teacher of all Christians.” So, in order to find salvation for your soul, added the Pope, you must follow the Mother Church, accept what She accepts, submit to the bishop and be taught and shepherded by him.

The answer of the truly Orthodox bishop lies within the enduring position of the Church and is in agreement with the Fathers. It is a word for word repetition, a thousand years later, of the stance of Athanasius the Great, whom we have mentioned, and of all the Holy Fathers who came after him: By the grace of God we are Christians and we accept and follow our Church. For our Church holds true to what it has received both from the teaching of Our Lord Jesus Christ and from the tradition of the Holy Apostles and of the ecumenical synods and of the holy teachers recognized by the Church; and it has never departed from their teaching nor has it added nor left anything to chance. But the Church of Rome has added to and transgressed the bounds of the Fathers. This is why we, who hold fast to the things of the Fathers, have cut it off or have removed ourselves from it. So, if your beatitude wishes to bring peace to the Church and unite us all, you must expunge the addition of the filioque from the Creed. You can do this easily, should you wish, because the nations of the Latins will accept whatever you suggest, since they consider you the successor to Saint Peter and respect your teaching.

Syropoulos’ conclusion: the Pope expected to lead by the nose and win over the Iberian with his false blandishments, given that the man was a foreign-speaker, an individual both unlearned and barbarian. “But, when he heard this answer, he was left speechless.”